- September 4, 2025

The Poet Mariachi: Finding Voice, Culture, and Empowerment in the Borderlands

When Macedonio García, Sr. sang while working in the fields of Texas, the West Coast, and beyond, he carried the spirit of Mexico’s great ranchera singers with him. A fan of Vicente Fernández, José Alfredo Jiménez, and Pedro Infante, he became known as “Chente” among family and friends. His love for song would ultimately shape his son’s path as a writer, educator, and performer. Today, that son—Daniel García Ordaz, known as The Poet Mariachi—continues his father’s legacy, blending poetry, music, and identity into an art form that empowers audiences across cultures.

Roots in Houston, the Valley, and Beyond

Raised between Houston and the Rio Grande Valley, García grew up observing the world quietly, his shyness giving way to a poetic voice. “After my dad passed away, my mom asked me to sing,” he recalls. “I sing to keep my father’s legacy alive.” That personal history grounds his art in both family and culture.

His intersecting identities—American, Mexican American, Tex-Mex, even “pocho”—inform not just his subject matter but his very language. He draws on Gloria Anzaldúa’s mestizaje, the borderland mixing of culture and tongue, and sees his voice as a reflection of the frontera itself. “I mix languages (Spanish, English, Tex-Mex, Caló). I mix genres. I mix food. I write like I live—in a multilingual world.”

Inspiration from Poets of Power

From Langston Hughes to Maya Angelou, Pablo Neruda to Walt Whitman, García’s influences are as layered as his own work. “Langston Hughes and Maya Angelou gave me rhythm and accessibility. Neruda taught me boldness. Whitman and Anzaldúa showed me how to embrace mestizaje.”

His poetry, like theirs, navigates the tension between play and power—sometimes comical, sometimes political, always musical. “At the end of the day, my poetry is about having fun with language,” he says.

Empowerment Through the Word

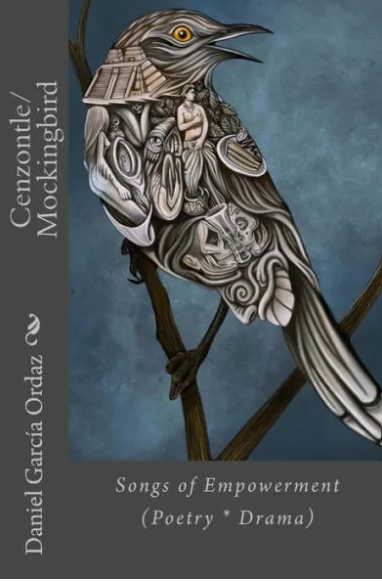

Central to García’s mission is empowerment. His collection Cenzontle/Mockingbird: Songs of Empowerment reminds readers that power already lives within them. “We live in a world that attempts to erase our culture, our voices. As Mexican Americans, we’re told we’re not enough of either identity. But songs and poetry give us the space to reclaim pride.”

His MFA thesis, Cenzontle/Mockingbird: Empowerment Through Mimicry, reframes mimicry as empathy. “I want people to TALK a mile in someone else’s voice,” he explains. “Mimicry is not mockery—it’s a way to get closer, to know one another, to respect our differences.”

The Educator and the Laureate

As a dual-enrollment college instructor, García brings poetry into every classroom. “Dr. King wasn’t a poet, but what made him such a powerful communicator? He used poetic tools. I teach my students to weave poetry into their arguments and essays.”

His role as McAllen’s Poet Laureate gave him more visibility but did not change his community mission. Before and after the title, García has dedicated decades to hosting workshops, readings, and festivals that center poetry as a tool for connection.

Building a Festival, Building a Community

In 2007, after organizing the first “Poetry Pachanga” at UT-Pan American, García co-founded the Rio Grande Valley International Poetry Festival. “Before, Valley poets had to travel to Austin or Houston for literary events. Now, we bring the world here.”

The festival continues to attract poets nationally and internationally, turning the 956 into a hub of literary exchange. One of García’s dreams is to restore cross-border readings with Tamaulipas, once central to the festival’s binational spirit.

Service, Healing, and Storytelling

García’s time as a U.S. Navy Hospital Corpsman shaped his perspective on language and humanity. “I promised God I wouldn’t take lives, so I became a healer. Serving with Marines, I worked alongside people from all over the world—Jamaica, Haiti, the Philippines. Their voices influenced mine. That’s where mimicry as respect took root.”

It was also during his Navy service that he began writing his first poems on duty, blending service with storytelling as a form of healing.

Writing for Young Readers

His latest book, Read Until You Bleed, offers young audiences humor, wordplay, and empathy. Written partly as a response to grief after losing his brother in a car accident, the collection uses humor as healing. “I treat kids as little humans who face real life. I give them big words, hard topics, and silliness. It’s all part of the mestizaje.”

Recognition and Reach

Though García has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and studied in academic circles—including by a scholar in China who wrote her dissertation on his poetry—he insists recognition is not the goal. “When we sing, we all win. When we create and write, we all win.”

What matters most are the students who approach him after a performance and say: I didn’t know I could use Spanish in my writing. For García, that is the impact—opening doors for others to embrace their full identity.

Looking Ahead

Beyond poetry, García continues to explore painting, photography, and songwriting. He hopes to share more of his music publicly, while also expanding his reach through author events in San Antonio and New York City.

For The Poet Mariachi, every performance, every festival, every poem is part of one larger project: keeping alive the voices of his community, his father, and his culture. “Poetry can heal,” he says. “It’s our shared humanity in words.”