- November 27, 2024

Ortega’s constitutional changes will turn Nicaragua into a tropical North Korea

Andres Oppenheimer

Nicaragua’s dictator Daniel Ortega has drafted a constitutional reform that may make his country the most repressive regime in the Americas — even worse than Venezuela and Cuba. It’s going to officially turn Nicaragua into a tropical North Korea.

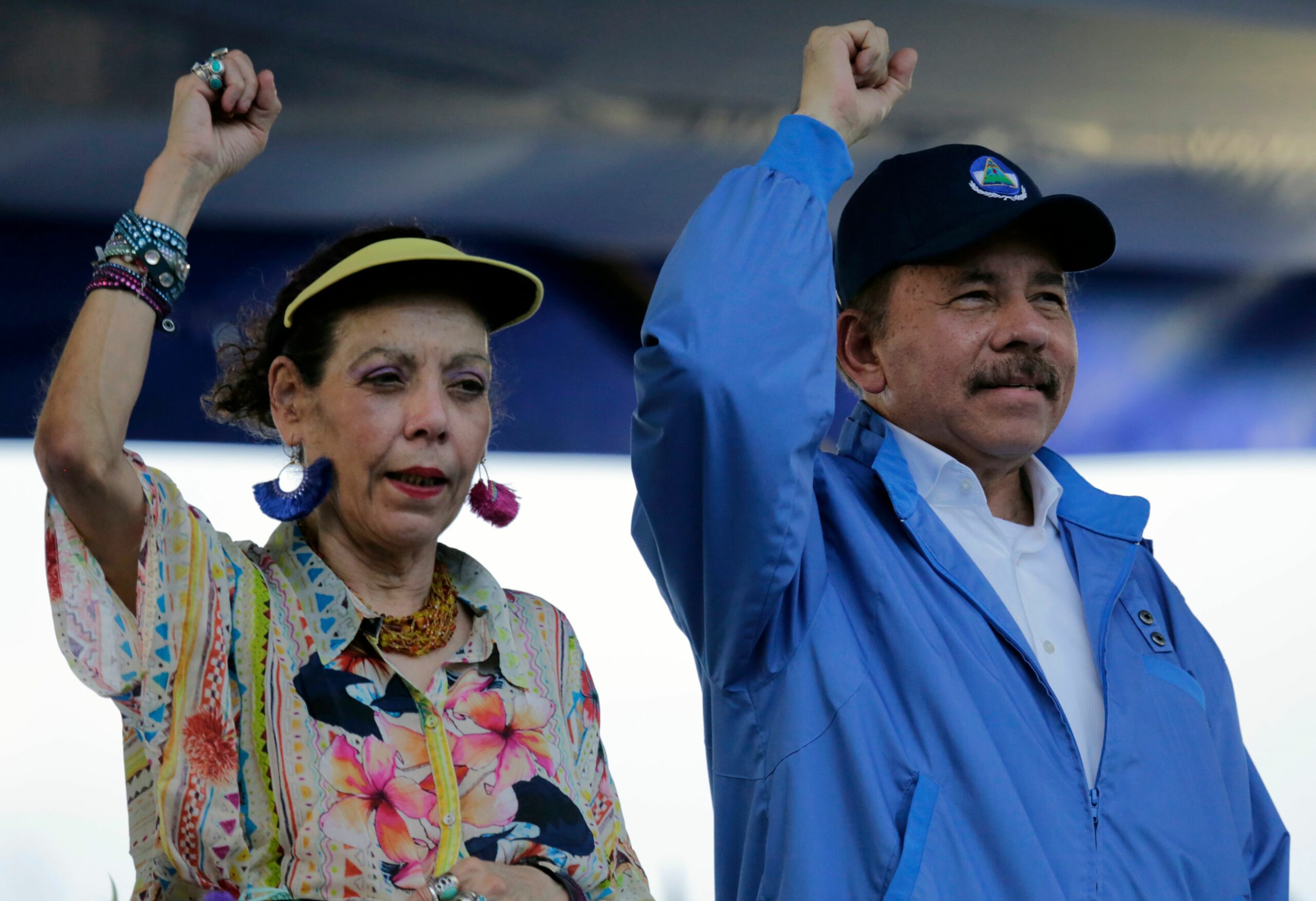

Ortega’s constitutional changes will, among other things, give legal cover for the government to arrest critics on charges of “treason to the fatherland,” and strip them of their citizenship. They will also make Ortega and his wife, current Vice President Rosario Murillo, “co-presidents,” with powers to “coordinate” all other branches of government.

The reform, consisting of dozens of constitutional amendments, was sent by Ortega to the government-controlled National Assembly on Nov. 20, and is almost sure to be approved. The ruling Sandinista National Liberation Front party and its allies control 84 of the National Assembly’s 90 seats.

“Nicaragua is already the most oppressive society in the hemisphere, worse than Cuba or Venezuela,” Juan Pappier, a senior Latin American analyst with the Human Rights Watch advocacy group, told me. “It’s becoming Latin America’s version of North Korea.”

While in Cuba and Venezuela you still have small numbers of independent journalists and human rights activists trying to do their jobs despite government repression, that’s become almost impossible in Nicaragua, Pappier told me.

Since massive street demonstrations in 2018, in which about 350 mostly peaceful protesters were killed by Ortega’s paramilitary squads and many more were arrested, the Ortega-Murillo regime has closed down about 5,000 non-government organizations. Many of them were charities run by the Catholic church.

The government has also stripped about 450 opposition politicians, journalists and human rights activists of their citizenship. Many of them have been branded as “traitors,” put on planes and sent to the United States.

Ortega doesn’t seem to be bothered by international criticism. When I interviewed him at length at his home in Managua in 2018, he shrugged off all criticism from human rights groups and the media. He claimed it was part of an alleged defamatory campaign against his country by the United States, and especially by Florida’s congressional delegation.

When I asked him if he doesn’t mind being called a dictator, he raised his shoulders, and responded with a smile, “The truth is, I’m used to being called all kinds of things.” On the number of street demonstrators human rights groups say his government killed in 2018, he said matter of factly, “It’s not 350, it’s 195.”

Under Article 1 of Ortega’s planned constitution reform, “anyone” who threatens the “sacred rights of the Nicaraguan people will be considered traitor to the fatherland.” Under Article 17, “traitors to the fatherland shall lose their Nicaraguan nationality.”

Among other highlights of Ortega’s 66-page reform plan, which carries his signature:

- It defines Nicaragua as a “revolutionary” country, and says that the state is based on a set of principles, including “socialist ideals.”

- It creates a “voluntary police,” which human rights groups say in effect will be a paramilitary force. Ortega in 2022 thanked an improvised “voluntary police” for the crackdown on street demonstrations that left hundreds dead.

- It says that the new Ortega-Murillo “co-presidency” will “head the government and coordinate the legislative, judicial, and electoral organs,” as well as autonomous agencies.

- It states that people will have the right to express themselves freely publicly and privately, “as long as” they don’t go up against “the principles enshrined” in the Constitution. In other words, criticizing “socialist ideals” could make political parties or independent news media illegal.

There are several theories about why Ortega, 79, may have drafted this constitutional reform, considering that he already controls all branches of government and has already carried out a brutal repression of domestic critics.

One possible theory is that he wants to give legal cover to his regime’s brutality. Another one is that — at the insistence of his powerful wife and vice president — he wants to prepare a legal pathway for Murillo’s takeover if he dies anytime soon.

Whatever it is, Nicaragua is on its way to becoming — constitutionally — the champion of Latin America’s repressive dictatorships. But, sadly, few are paying attention to it.